- Aimé Césaire – Cahier d’un retour au pays natal

- Bernard Dadié – Un nègre à Paris

- Bernard Dadié – Patron de New-York

- Bernard Dadié – La ville où nul ne meurt. Rome

- Williams Sassine – Wirriyamu

- Ken Bugul – Le baobab fou

- Sembene Ousmane – Le docker noir

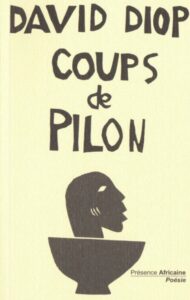

- David Diop – Coups de pilon

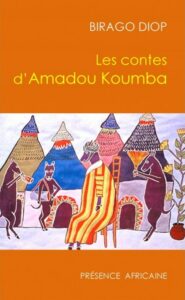

- Birago Diop – Les contes d’Amadou Koumba

- Jacques Rabemananjara – Les Dieux malgaches

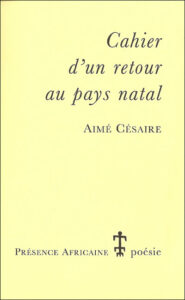

Aimé Césaire – Cahier d’un retour au pays natal

– Poetry –

|

Summary: Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (first published in 1939, with two revised editions in 1947 and the current final edition in 1956), variously translated as Notebook of a Return to My Native Land, Return to My Native Land, or Journal of a Homecoming, is a book-length poem by Martinican writer Aimé Césaire, considered his masterwork, that mixes poetry and prose to express his thoughts on the cultural identity of black Africans in a colonial setting. According to Bonnie Thomas, Cahier d’un retour au pays natal was a turning point in French Caribbean literature: « Césaire’s groundbreaking poem laid the foundations for a new literary style in which Caribbean writers came to reject the alienating gaze of the Other in favour of their own Caribbean interpretation of reality. » André Breton called the poem « nothing less than the greatest lyrical monument of our times. » |

|

|

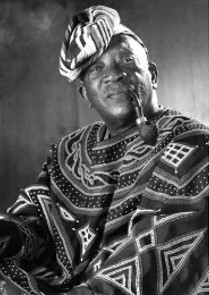

Publication: Présence Africaine, 1956 Bio: Aimé Césaire (26 June 1913 – 17 April 2008) was a French poet, author, and politician. He was « one of the founders of the Négritude movement in Francophone literature » and coined the word négritude in French. He founded the Parti progressiste martiniquais in 1958, and served in the French National Assembly from 1945 to 1993 and as President of the Regional Council of Martinique from 1983 to 1988. His works include the book-length poem Cahier d’un retour au pays natal (1939), Une Tempête, a response to Shakespeare’s play The Tempest, and Discours sur le colonialisme (Discourse on Colonialism), an essay describing the strife between the colonizers and the colonized. His works have been translated into many languages. Link to the book on Présence Africaine: Here Rights inquiries: Here |

|

Notebook of a Return to My Native Land / Cahier d’un retour au pays natal, trans. Mireille Rosello with Annie Pritchard (1995)

|

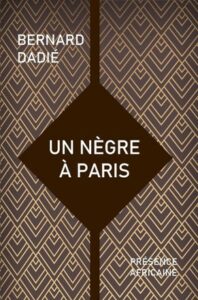

Bernard Dadié – Un nègre à Paris

– Novel –

|

Summary: A West African man’s first journey to France, from the exhilarating moment when he obtains his ticket through a humorous and fascinating tour across the City of Light. In 1959, when Un Negre a Paris first appeared, the French still held West Africa under colonial rule. Dadié’s subtle parodies draw on intimate knowledge obtained over decades spent observing the colonizers abroad and now, suddenly, on their own home terrain. His remarks on Parisian living conditions, wordplay, manners, and and morals are entertaining and poignant, charming yet profound. New 2023 French edition. |

|

|

Publication: Présence Africaine, 1959 Bio: Bernard Binlin Dadié, considered the revered father of Ivorian literature, left a rich and diversified legacy. Born in Assinie, Ivory Coast, his journey, marked by political engagement and a prolific body of work encompassing poetry, novels, theater, chronicles, and traditional tales, constitutes an indelible contribution to African culture. His life was a saga of activism, resistance, and public service. The pages of his prison journal, published in 1981 under the title Carnets de prison, reveal his courage during the February 1949 troubles. Minister of Culture and Information in 1977, he was honored with prestigious awards, including the Grand Prix littéraire d’Afrique noire in 1965 and the UNESCO/UNAM Prize in 2016. Un nègre à Paris (An African In Paris) was translated into English by Karen C. Hatch and published by Illinois University Press in 1994. Link to the book on Présence Africaine: Here Rights inquiries: Here |

© Présence Africaine |

Bernard Dadié – Patron de New-York

– Novel (Chronicle) –

|

Summary: The travel chronicle written in 1963 by Bernard Dadié. It is a time of resistance, uprisings, and struggles for freedom across Africa and its diaspora in the United States. The narrative depicts the adventure experienced by an African during his first trip to New York. As an educated and observant man, Dadié shares his impressions, sometimes humorous and sometimes dark, but always indicative of his commitment to justice. The novel was awarded the Grand prix littéraire d’Afrique noire in 1965. New 2024 French edition. |

|

|

Publication: Présence Africaine, 1964 Bio: Bernard Binlin Dadié, considered the revered father of Ivorian literature, left a rich and diversified legacy. Born in Assinie, Ivory Coast, his journey, marked by political engagement and a prolific body of work encompassing poetry, novels, theater, chronicles, and traditional tales, constitutes an indelible contribution to African culture. His life was a saga of activism, resistance, and public service. The pages of his prison journal, published in 1981 under the title Carnets de prison, reveal his courage during the February 1949 troubles. Minister of Culture and Information in 1977, he was honored with prestigious awards, including the Grand Prix littéraire d’Afrique noire in 1965 and the UNESCO/UNAM Prize in 2016. Patron de New-York (One Way: Bernard Dadié Observes America) was translated into English by Jo Patterson and published by Illinois University Press in 1994. Link to the book on Présence Africaine: Here Rights inquiries: Here |

© Présence Africaine |

Bernard Dadié – La ville où nul ne meurt. Rome

– Novel –

|

Summary: In this witty and ironic reversal of the typical colonial travelogue, Dadié recounts the journey of a bemused African traveler who settles in Rome, continuing his inquiries into the fundamental nature of humankind. Part conqueror, part pilgrim, part worshipper, and part critic, the protagonist compares Roman and African customs, traditions, history, and, above all, personalities. Dadié’s account of the rewards and pitfalls of exploring other cultures is spiced with generous enthusiasm and respect for life and all its eccentricities. First published in French in 1968. New 2023 French edition. |

|

|

Publication: Présence Africaine, 1968 Bio: Bernard Binlin Dadié, considered the revered father of Ivorian literature, left a rich and diversified legacy. Born in Assinie, Ivory Coast, his journey, marked by political engagement and a prolific body of work encompassing poetry, novels, theater, chronicles, and traditional tales, constitutes an indelible contribution to African culture. His life was a saga of activism, resistance, and public service. The pages of his prison journal, published in 1981 under the title Carnets de prison, reveal his courage during the February 1949 troubles. Minister of Culture and Information in 1977, he was honored with prestigious awards, including the Grand Prix littéraire d’Afrique noire in 1965 and the UNESCO/UNAM Prize in 2016. La ville où nul ne meurt. Rome (City Where No One Dies) was translated into English by Janis A. Mayes and published by Three Continents Press in 1986. Link to the book on Présence Africaine: Here Rights inquiries: Here |

© Présence Africaine |

– Novel –

|

Summary: In this novel, Williams Sassine recounts the details of an actual massacre in the village of Viramo at the hands of the Portuguese soldiers in December 1972, in which he focuses on the character of the black-haired, black-eyed Kondillo, whose aim is to kill and crucify him. Audrey Small: « A violent and violated rural landscape becomes emblematic of a specific traumatic event occurring within the time frame of the novel and of contemporary political reality. » New English edition forthcoming in 2024. |

|

|

Publication: Présence Africaine, 1976 Bio: Williams Sassine (1944 in Kankan, Guinea – February 9, 1997 in Conakry, Guinea) was a Guinean novelist who wrote in French. His father was Lebanese Christian and his mother was a Guinean of Muslim heritage. Sassine was an expatriate African writer in France after leaving Guinea when it received independence under Sékou Touré. As a novelist he wrote of marginalized characters, but he became more optimistic on Touré’s death. His 1979 novel Le jeune homme de sable has been regarded as among the best 20th-century African novels. As an editor he remained critical of Touré as chief editor for the satirical paper Le Lynx. Some of Sassine’s works have been translated into English, Spanish, German, Slovene, Arabic, Polish, Turkish and Russian. Link to the book on Présence Africaine: Here Rights inquiries: Here |

|

– Novel –

|

Summary: Abandoned by her mother and sent to live with relatives in Dakar, the author tells of being educated in the French colonial school system, where she comes gradually to feel alienated from her family and Muslim upbringing, growing enamored with the West. Academic success gives her the opportunity to study in Belgium, which she looks upon as a « promised land. » There she is objectified as an exotic creature, however, and she descends into promiscuity, alcohol and drug abuse, and, eventually, prostitution. Her return to Senegal, which concludes the book, presents her with a past she cannot reenter, a painful but necessary realization as she begins to create a new life there. As Norman Rush wrote in the New York Times Book Review, « One comes away from Le Baobab fou reluctant to take leave of a brave, sympathetic, and resilient woman. » The book was chosen by QBR Black Book Review as one of Africa’s 100 best books of the twentieth century.

|

|

|

Publication: Présence Africaine 1991 Bio: Ken Bugul, which in Wolof means: « the person no one wants », is the pseudonym used by writer Mariètou Mbaye Biléoma who was born in 1947 in Ndoucoumane in Senegal. Following her primary school studies in her village, Mariètou Mbaye undertook her secondary schooling at the Lycée Malick Sy at Thiès, after which she spent a year at the University of Dakar from where she obtained a bursary that enabled her to continue her studies in Belgium. From 1986 to 1993, Mariètou Mbaye was an International Official, based successively in Nairobi (Kenya), Brazzaville (Congo), Lomé (Togo) as Head of Programs within the African Region of the IPPF (International Planned Parenthood Federation), a NGO concerned with projects related to family planning. Her novel Riwan ou le chemin de sable [Riwan or the sandy track] was awarded the 1999 prestigious literary prize Grand Prix littéraire de l’Afrique noire. Her work has been translated into many languages: English, Italian, Dutch, German, Polish, Spanish, Slovene. Link to the book on Présence Africaine: Here Rights inquiries: Here |

|

Sembene Ousmane – Le docker noir

– Debut Novel –

|

Summary: Set in the 1950s in Marseille, this book tells of Diaw Falla, a docker for whom work exists merely to finance his true obsession – his writing. As his novel nears completion, he meets Ginette Tontisanne whose good connections ensure he is published – but, to his dismay, under her name… The black docker is a long cry of bitterness in which a passionate desire for justice erupts. It is also a warning, a first-hand document on the lives of black minorities lost in major European cities. French edition to be reissued in 2023, for Sembene Ousmane’s 100th year birth anniversary. |

|

|

Publication: Présence Africaine, 1956 Bio: Ousmane Sembène (1 January 1923 or 8 January 1923 – 9 June 2007), often credited in the French style as Sembène Ousmane in articles and reference works, was a Senegalese film director, producer and writer. The Los Angeles Times considered him one of the greatest authors of Africa and he has often been called the « father of African film ». Descended from a Serer family through his mother from the line of Matar Sène, Ousmane Sembène was particularly drawn to Serer religious festivals especially the Tuur festival. Link to the book on Présence Africaine: Here Rights inquiries: Here |

© Présence Africaine |

David Diop (Senegal) – Coups de pilon

-Poetry, 1956 –

|

Summary: It is rare that the control of the verb and the depth of the emotion are combined, that the distance and the gift agree. In this paradoxical harmony, the best is revealed. The word of David Diop testifies to this admirable and difficult place. David Diop knew Africa by heart, in its depths, in its living sources, in its people, that is, in its truth. He knew it in its fragility and its caricatures, avatars of an Africa sold and exploited at the markets of history. The poet lived this tension, heavy with this suffering, but carried forward by the hope that the vitality of the peoples of Africa inspires. This dual postulation marks his approach as a committed Negro-African writer, lucid and rigorous in his fight. That’s why these beautiful and proud texts remain so close to us, fraternal and always exemplary. English translation to be reissued in 2023. |

|

|

Publication: Présence Africaine, 1956 Bio: David Mandessi Diop (9 July 1927 – 29 August 1960) was a French West African poet known for his contribution to the Négritude literary movement. His work reflects his anti-colonial stance. Diop started writing poems while he was still in school, and his poems started appearing in Présence Africaine since he was just 15. Diop lived his life transitioning constantly between France and West Africa, from childhood onwards. While in Paris, Diop became a prominent figure in Négritude literature. His work is seen as a condemnation of colonialism, and detest towards colonial rule. Like many Négritude authors of the time, Diop hoped for an independent Africa. Within the movement he was recognized as « the voice of the people without voice ». He died in the crash of Air France Flight 343 in the Atlantic Ocean off Dakar, Senegal, at the age of 33 on 29 August 1960. His one collection of poetry, Coups de pilon, came out from Présence Africaine in 1956; it was posthumously published in English as Hammer Blows, translated and edited by Simon Mondo and Frank Jones (African Writers Series, 1975). It was subsequently published and translated in Italian in 1979 at Jaca Book (Canti di lotta e di speranza, translation Cristina Brambilla). Link to the book on Présence Africaine: Here Rights inquiries: Here |

© |

|

Birago Diop (Senegal) – Les contes d’Amadou Koumba

– Tales, 1961 –

|

Summary: The nineteen traditional folk tales in this collection have been retold in French by the Senegalese writer Birago Diop. Diop claims that these tales were recounted to him by his household griot Amadou, son of Koumba, and that he first heard them at his grandmother’s hut where he was born, told in Woloff, the local dialect. Translated into 12 languages. |

|

|

Publication: Présence Africaine, 1961 (first edition 1947) Bio: Birago Diop (11 December 1906 – 25 November 1989) was a Senegalese poet and storyteller whose work restored general interest in African folktales and promoted him to one of the most outstanding African francophone writers. A renowned veterinarian, diplomat and leading voice of the Négritude literary movement, Diop exemplified the « African renaissance man ». Link to the book on Présence Africaine: Here Rights inquiries: Here |

© Présence Africaine |

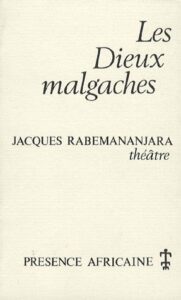

Jacques Rabemananjara (Madagascar) – Les Dieux malgaches

– Play, 1988 (first edition 1964) –

|

Summary: The Malagasy Gods begins in an exotic setting with an exchange of gallantries and love dialogues between the King and his beloved. A play invented and based on a true story: the battle between two cultures (traditional and modern). Written in the French language, which is subject to the will of Rabemananjara and the strength of Malagasy, the play’s dialogues give a glimpse of Malagasy society and its culture. The mysterious power of royal authority and Rabemananjara’s skilled pen give « The Malagasy Gods » a historical and political dimension. Drawing parallels with contemporary Malagasy society, the play highlights that many aspects were already evident in both the people of today and the play itself. Summary courtesy: M Y R |

|

|

Publication: Présence Africaine, 1988 Bio: Jacques Rabemananjara (23 June 1913 – 1 April 2005) was a Malagasy politician, playwright and poet. He served as a government minister, rising to Vice President of Madagascar. Rabemananjara was said to be the most prolific writer of his negritude generation after Senghor, and he had the first négritude poetry published. Link to the book on Présence Africaine: Here Rights inquiries: Here |

© Présence Africaine

|

© Présence Africaine

© Présence Africaine

© Présence Africaine

© Présence Africaine © Georges Seguin (creative commons)

© Georges Seguin (creative commons)